Below is some insight into the Victorian apothecary. Early in the period, apothecaries were considered doctors as not only did they prepare medicines and remedies for patients, but they also treated patients, dressed wounds and performed minor surgeries for a fee. Skill in chemistry was an important part of the apothecary's identity, and these jars- which contained the ingredients used to manufacture medicines- leant prestige to their craft. These practices were broadly comparable across Western and Northern Europe at this time, but in colonial North America medical treatment was patchier, and the. Both Yeoman and Bell believed in several types of bath ranging from cold to hot, and they found many instances where bathing was beneficial. In fact, Bell claimed there was “ample historic precedent and contemporaneous usage in bathing’s favour.”2 Bell also stated that cold baths helped “various febrile diseases,” inflammation of the joints, injuries from sprains and fractures.

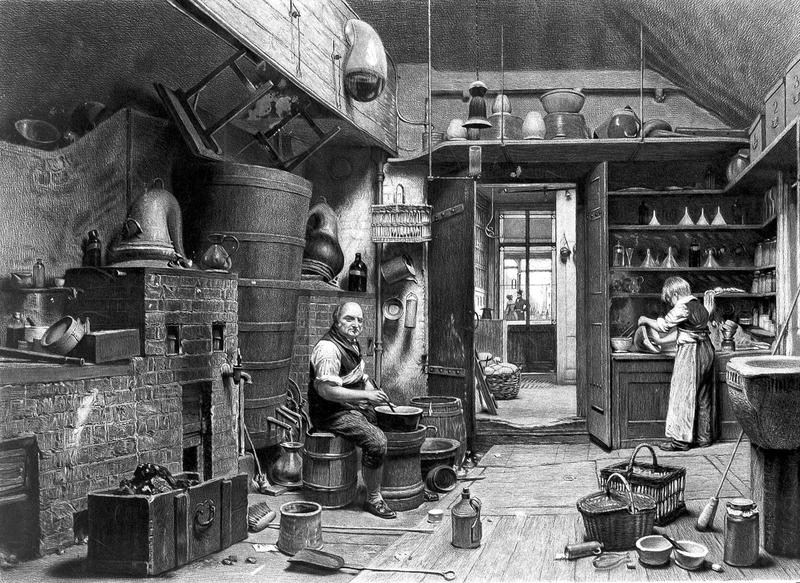

An apothecary and his apprentice working in the laboratory of John Bell's pharmacy. Engraving by J.G. Murray, after W.H. Hunt, 1842. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (CC).

British law at the beginning of the eighteenth century enforced the monopolies of the tripartite system of medical professionals, and in theory regulated their activities. However, by this time the system was under pressure, and boundaries of practice were shifting. The low numbers of elite physicians in comparison with market demand for medical care meant that the public were turning to apothecaries as a more readily available- and cheaper- alternative. Due to this imbalance in care, as well as overcrowding amongst the apothecaries, the old hierarchy began to give way. A turning point came when the Rose Case of 1704 approved this custom in law and gave apothecaries the freedom to practice physic as well as pharmacy. Throughout the eighteenth century, English apothecaries therefore developed into a group calling themselves general practitioners (and indeed, resembling modern-day GPs), and divisions between the tripartite professions further broke down. By the end of the century, the surgeon-apothecary treated a wide range of social classes. As they were not educated to the same level as the physician (nor did they share their social status) they were a great deal cheaper and were thus used more widely by the general populace for medical care.

By the 1800s the role of the apothecary had changed considerably. Whilst some apothecaries were still involved in the dispensing and mixing of drugs, few did so from a retail perspective and instead charged patients directly for remedies during clinical visits. The retail aspect of medical practice had now fallen to a separate group, the chemists and druggists. The Regency and Victorian druggists ran their profitable businesses from a street shopfront, and like seventeenth-century apothecaries, were involved in the on-site manufacture of their own medicines. They also took on an advisory role for those members of the lower and middle classes who could not afford the expensive care of a physician, but who were literate in the kinds of drugs needed to treat minor ailments. The druggists were entrepreneurial as well as medical, businessmen as well as trained practitioners. They successfully saw and filled a gap in the market left by the transition of the surgeon-apothecary to general practitioner; namely, an opportunity to sell drugs cheaply and undercut the prices charged by this new rank-and-file physician.

The Physician's Verdict. Oil painting by Emile Carolus Leclerq, 1857. Image courtesy of the Wellcome Collection (CC).

Unsurprisingly, a rivalry developed between the apothecary-GPs and the chemist-druggists over professional turf, particularly in regard to dispensing physicians' medicines. The apothecary-GPs’ desire to establish professional distinction led to agitation for legal reform and, eventually, to legal regulation of the medical community. Between the 1815 Apothecaries Act and the 1858 Medical Act, the practice of medicine became regulated in Britain. Apothecaries became subject to rules regarding training, licensing, and practice. Chemists and druggists were excluded from this licensing, but defined as a distinct profession with their own jurisdiction. Towards the middle of the century, they began pushing for their own regulatory body in order to prevent charges of quackery, and reinforce their medical status. This culminated in the founding of the Pharmaceutical Society in 1841. Schools were then set up to teach pharmacy, and the Pharmacy Acts of 1852 and 1868 helped to regulate the sale of pharmaceuticals, and create uniform standards of training and examination. However, not all chemists and druggists educated themselves in this way, and many continued to learn the ropes via apprenticeship until late in the nineteenth century.

By the mid-1800s, the English chemist and druggist were well-established professionals, defined by their work in a wholesale and retail capacity, and catering to a population before, instead of, or in addition to, the intervention of a GP. Their services were wide ranging and competitive; they sold a variety of items, from toiletries and food to ointments and pills, and were appealing to a paying customer who (at least in the cities) had a choice of establishments to patronise. Despite this, many succeeded in making an excellent living, and had a high standing within their communities. Broadly, they functioned as a medical “first-port-of-call” for many different social classes.

At a Neanderthal burial site at Shanidar Cave, Iraq, discovered in 1960, archaeologists found the body had been buried with eight species of medicinal plants. This site is some 60,000-80,000 years old.

The first pictorial evidence of herbal medicine, on the walls of the Lascaux Caves in France, was radiocarbon dated to between 13,000 to 25,000 BC.

In the Swiss Alps in 1991, the 5,300 year old Otzi Iceman’s body was found and strung round his waist was the birch fungi Piptoporus betulinus. Birch fungus contains antibiotic and antibacterial properties and may have been used to treat intestinal parasites.

Around 3000 B.C., willow bark was recorded on a stone tablet of medical remedies from the Third Dynasty of Ur, and was mentioned again on the Ebers Papyrus around 1543 B.C.

Pen Ts’ao or The Canon of Herbs attributed to Emperor Shen Nung (who died in 2698 B.C.) documented the early Chinese use of herbs. It included 252 plant descriptions and describes their medicinal effects, how and where to grow them and how to use and preserve them.

Bronze Age people were certainly using herbal medicines. Cists and burial sites dated to 1000 and 2000 B.C. have found evidence of medicinal herbs being left with the bodies. Birch bark and meadowsweet are indigenous to the UK and would have been a natural choice of herbal medicine brewed as teas or, in the case of meadowsweet, incorporated into mead – the local alcohol of choice! UK sites where meadowsweet has been found include: Fan Foel in Wales; and Fort Teviot, Ashgrove, North Mains in Scotland. Cypress was found in dental remains in the Shetland site of St. Ninians, and in some indigenous people (e.g. Israeli Arabs) it is used like clove oil is, for treating gum bleeding and toothache.

Hippocrates 460-377 B.C. often called the Father of Modern Medicine, was one of the first physicians to separate health and medicine from superstition, and his philosophy was based on “vis medicatrix naturae” or “the healing power of nature”. He published many works on diagnosis, on how a physician should conduct himself and his practice

Pedanius Dioscorides 40-90 A.D., physician, botanist and pharmacologist, published a five-volume De Materia Medica in Greek documenting around 600 plants with medicinal usage. This was used as a definitive herbal reference book until the 1600s.

Claudius Galen 131 – 200 A.D.

Victorian Apothecary Remedies Spray

754 A.D. is when the first apothecary, offering both herbal and some chemical remedies as well as medical advice, is reputed to have opened. These grew and spread from the Muslim to the Western world and were certainly in England by Geoffrey Chaucer’s time (1342-1400). He writes in The Nun’s Tale:

“And in this town there’s no apothecary,

I will myself go find some herbs for you

That will be good for health and pecker too;

And in our own yard all these herbs I’ll find,

The which have properties of proper kind”

and later mentions some herbs by name:

“Of laurel, centuary, and fumitory,

Or else of hellebore purificatory,

Or caper spurge, or else of dogwood berry,

Or herb ivy, all in our yard so merry;”

Ibn Sina, corrupted to Avicenna, 980 – 1037 A.D. was a Persian physician who combined the teachings of Dioscorides and Galen with the Islamic herbal traditions of his own people. Amongst other publications, he wrote The Book of Healing and also, al-Qanun fi at-tibb or The Canon of Medicine, one of the most influential medical books ever, which was adopted throughout Europe during the 11th and 12th centuries. This early pharmacopoeia listed around 800 herbs and minerals, recording their use and effect.

Hildegard of Bingen 1098 to 1179 was a German abbess and saint who wrote several books on herbal medicine such as Cause and Cure and Physica. Like many of the educated clergy and religious of the time she also practiced as a herbalist.

Victorian Apothecary Remedies For Sale

In the early 13th century, Rhys Gryg ( warrior son of Welsh Prince Rhys ap Gruffydd) was Lord of Dynevor and Ystrad Towy. He had his own personal ‘physician’ called Rhiwallon who passed on his knowledge to his three sons; Cadwgan, Gruffydd and Einion. They lived in the small village of Myddfai in Carmarthenshire. The last physician descended from this family, Rice Williams, died in 1842. The physicians of Myddfai used a materia medica of around 175 locally grown herbs.

From the 14th century, the Beatons of Mull (also McBeaths, or MacBeths – the name changed over the centuries) or ‘Ollamnh Muileach’ were the traditional herbalists and healers for The Lords of the Isles, the Macleans of Duart, and later, for the Kings of the Scots. They originated in Béthane, France, and came to Scotland via Celtic Ireland during the reign of Angus of Islay who died around 1316. For several generations and centuries, the Beatons ran a very effective health service for the kings, the lords, the clan chiefs and their followers. They had a great library including the works and teachings of Avicenna in Gaelic, Averroes, Joannes de Vigo, Bernardus Gordonus, and several volumes of Hippocrates. A cairn cross was raised in 1582 to commemorate some of the doctors. A Royal Charter of 1609 issued in Edinburgh declared Fergus Beaton the Principal Physician to the Isles. The family’s last recorded Royal Physician, Fergus Beaton of Islay, died in 1628 and the last of the Beaton doctors died at the end of the 18th century.

Paracelsus 1493 – 1541 physician and botanist. His full name was Philippus Theophrastus von Hohenheim. He pioneered the use of chemicals and minerals in medicine as well as plants, from which he created derivatives like laudanum (opium tincture). It could be claimed that this was the first beginnings of pharmaceutical medicine and toxicology. He was also a practicing astrologer, as were many trained physicians of the time.

Victorian Apothecary Remedies Natural

In 1552, John Hamilton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, was brought low again by his severe asthma. Doctors could not cure him, although they tried all the strongest medicines in their repertoire. A travelling Italian Herb Doctor, Candoro, prescribed infusions of coltsfoot and other herbs, to use kelp in his pillow and not feathers, and have a sparse diet. He was also advised to give up his practice of having sex every day both before and after supper. John Hamilton was cured of his asthma (probably the main reason was giving up his feather pillow), but the doctors accused Candoro of witchcraft, and he narrowly escaped with his life.

During the 1500s, the rise of chemical medicine continued. There was a pressing need to find a cure for syphilis which was epidemic in Europe at the time. Physicians took the work of Paracelsus, who believed that minute doses of poisonous substances could provide a cure, to the limit. They used like arsenic, copper sulphate, iron, mercury, and sulphur, and where minute doses did not work, increased the doses to such an extent that poisoning was a common side effect of treatment. Initially herbal medicine did not seem to have a treatment for syphilis until the discovery of Guaiacum resin from the West Indies, discovered around 1533 and in use as a syphilis treatment by 1580.

The rise in power of the physicians, with their new chemical medicines, and surgeons, with bloodletting and leeches, put a lot of pressure on herbal medicine as they sought to discredit it. Apart from a genuine search by some to investigate and increase their understanding of medicine, for many the key driver was financial. With uneducated ‘simple’ country people having access to a whole range of self-treatments with herbs (known as simples), it was hard to persuade people to spend money on a cure. By discrediting herbal knowledge as folklore and superstition, the physicians rose in status, wealth and power.

In 1590 Agnes Simpson of Keith was burned at the stake for using herbs to alleviate the pains of childbirth.

During this time though, many herbals were written that are still famous today. In 1526, an anonymous herbal, the Grete Herball was written – in English not Latin – making it available to all classes in society. In 1597 John Gerard also wrote The Herball or General History of Plants in English. By 1653, Nicholas Culpeper, author of The English Physician Enlarged now commonly known as Culpeper’s herbal was actively championing herbal medicine and crossing swords with the medical establishment.

Victorian Apothecary Remedies Reviews

During the 17th and 18th centuries the different medical disciplines co-existed. However, the rise of city living, with their concentrations of wealth, also denied many people access to plants, that they would have gathered themselves in rural villages. The dependence on physicians and pharmacists grew steadily. However, partly inspired by American herbalists who visited Britain and gave public lectures, herbal medicine continued to be of interest. For many people herbal medicine was far more affordable that the physicians medicines, and many people feared their terrible side-effects. Laudanum (opium) addiction was widespread even n toddlers and children. Drugs such as Calomel (mercury chloride) could result in death, such as that of the US President George Washington. Arsenic poisoning was also commonly documented in the Victorian era as it was often used in dyes for clothes and paints, as well as being used to treat everything from malaria to syphilis to psoriasis. It was a common ingredient in tonics such as Fowlers Solution.

Famous British herbalists from the Victorian era, whose reputation has survived the test of time include:

John Boot 1815-1860 Boot was the founder of the huge modern day Boot’s chemist chain. What is less commonly known is that Boot was a herbalist and the business started as a herbal company. Boot’s mother used herbs for healing and may have taught him the remedies from such publications as John Wesley’s herbal Primitive Physic. In 1849 he and his wife opened a shop in Nottingham calledThe British and American Botanic Establishment. In 1871 his son Jesse joined his mother in the business which became M. and J. Boot, Herbalists. In 1884 he brought in the first pharmacist as he was selling patent medicines alongside the herbal preparations. Marrying in 1885, his wife Florence, daughter of a stationer, brought stationary and other goods to the business, and with her he developed a department store concept. In 1888 he renamed the company as Boots Pure Drug Company. By 1893 he had 33 stores and by 1900 there were 250. The rest is, as they say, history.

Founded in 1812 as English drug merchants, Potter and Clarke Ltd of 60 Artillery Lane, London published a Yearbook of Pharmacy in 1879 and the Potter’s New Cyclopaedia of Medicinal Herbs and Preparations in 1907 as a scientific reference book. By 1950 it had reached its 6th edition and many editions have been republished over subsequent 50 years. Now, Vifor Potters Ltd and owned by Galenica, Potter’s are still a principal manufacturer of herbal medicine in the UK.

Heath and Heather are another notable supplier of herbs from the turn of the century.

Duncan Napier 1831-1921, renowned Victorian herbalist and founder of Medical Botany in Edinburgh, opened his herbal shop and clinic on 25 May 1860 to provide the people of Edinburgh with affordable herbal medicine. Initially self-taught, he was a prominent member of the Edinburgh Botanical Society and achieved Registration as a Chemist and Druggist in 1878. He was elected a Member of the Medical Reformers of Britain in 1879. His sons and grandson joined the business which remained Napiers and Sons until the death of John Napier. In 1989, Napiers was acquired by Medical Herbalist, Dee Atkinson BA (Hons), MNIMH, MCPP and is now owned by Dee and Monica Wilde. Today Napiers the Herbalists runs clinics and shops in Edinburgh and Glasgow, seeing around 22,000 patients a year.

William Henry Box 1845-1916. WH Box was consumptive in his teens and the doctors had given up hope. His search for a herbal cure resulted in a dramatic cure and started studying herbs in his spare time. He gave up his career at the age of 30 to devote himself entirely to herbalism. He later wrote ìI had a strong impression that there was something in nature that would cure me and eventually the herbs I fixed upon were gathered and prepared. In the course of a few weeks I mended so wonderfully that I was able to return to my work”. In 1875 WH Box opened his first shop in St Teath, Cornwall and started manufacturing Box’s Far Famed Indigestion Pills. His manufacturing business, originally called the Giant Pill Manufactory, may have been based in nearby Delabole. In 1888 his expanding business moves to premises at 161 King Street, Plymouth. The slogan above the door read “Box’s Pills Save Doctors’ Bills”. By this time he had 30 people were employed.

William Box also published various books and tracts, such as: The Famous Bird That Speaks One Word – Quack 1910/1911. Wellcome Library. The Shameless Analysis of Secret Remedies by the British Medical Association analysed and exposed by WH Box, 161 King Street, Plymouth 1914. Price tuppence. It was written as a riposte to a BMA publication of 1912. He also wrote Dragged to Light and many pamphlets and herbal booklets.

His ‘Box’s Pills’ and ‘Golden Fire Liniment’ for rheumatism won Gold Medals in the Paris Exhibition of 1914 and a Diploma of Merit at the Rome Exhibition. These pills, known as Box’s Far-Famed Indigestion Pills were first manufactured in 1875, are one the traditional herbal remedy licenses still held by Rickard Lane’s today. Current remedies include Cut-A-Cough and Sage & Garlic Catarrh Remedy.

Henry Lane 1855-1911 In 1888 Henry Lane opened a Botanic Drug Store in Old Market Street, Plymouth. After his death his widow, Mrs Lane, carried on the business at 1 & 5 Market Street, and possibly his son after her. In 1954 it was acquired by his apprentice E.J. Rickard who had opened his own herbal shop in 1939 in Saltash Street. In 1965, Rickard Lane’s, having moved to Mayflower Street in 1963, merged with the surviving business of W.H Box to form Rickard Lane’s and WH Box Ltd.

Mrs Maud Grieve 1858–1941. Sophia Emma Magdalene Grieve (Neé Law) and known as Maud, wrote A Modern Herbal documenting the use of herbs in 1931 together with her editor, Hilda Leyel who was the founder of the Society of Herbalists It has remained in popular use in particular as it is available on the internet. She founded a herbal school and farm, where she trained many people. Her writing career started in World War 1 when she wrote many booklets, to help supply information about herbal medicine during the struggle with the wartime shortage of medicines. She was a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society, President of the British Guild of Herb Growers, and Fellow of the British Science Guild.